Chapter 2, Part 2 - Te Wao Nui a Tane

The Realm of Tane the Forest God

Please enjoy listening to 'taku putorino' by hirini melbourne featuring hinewehi mohi while reading chapter 2, part 2

Many years ago on one of the southern islands, close to where my friends had heard the call of Hākuwai, I was very excited to be shown a native bat, or pekapeka. Ever since, I have been intrigued by this rare and delicate creature. Our two species of bat are the only land mammal indigenous to Aotearoa, and as they are so different I appreciate the myth that explains their presence here.

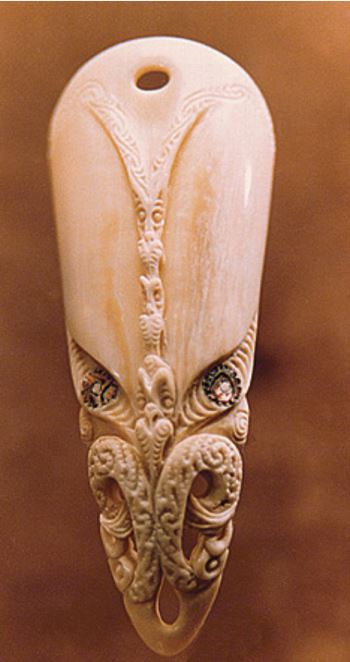

Pekapeka carving

When Tāne was climbing through the heavens to obtain the kete of knowledge he was beset by the terrible hordes of his jealous brother Whiro, who wished he had been chosen for the task. Among these attackers were mosquitoes, sandflies and bats, and the latter became adopted children of Tāne. They are sometimes now so loved that they become kaitiaki for certain people. An interesting traditional style of pendant is known as pekapeka, though the name could be a generic one for a branching style of pendant, rather than a depiction of a bat. Sometimes I have used pekapeka to tell personal stories. The carving below depicts the spirits of two great musician friends, Hirini Melbourne and Richard Nunns. Each is holding one of their taonga pūoro, with whakapapa notches and manaia faces representing the support they drew from elders and ancestors.

Pekapeka carving representing Hirini Melbourne and Richard Nunns

I often use pekapeka to illustrate the important concept of balancing the spiritual and physical halves of our being. An acquaintance of mine once asked an Indian guru why meditation did not work for him. With great wisdom, the guru suggested that my friend should instead consider nourishing his spirit by going to his workshop to make a lot of noise and create a prayer wheel to put in his stream. This understanding of the differences of the human spirit allowed me to appreciate how diverse our spiritual natures are, something I try to reflect in my carvings

Variations on the pekapeka theme

Like the bat, New Zealand native frogs are also enigmatic creatures unique to this country. Native frogs are unusual as they are almost silent, and do not go through a free-swimming tadpole stage, with the froglets riding around on their father’s back as they grow. I know of one place where frogs are a family kaitiaki, but their place in tradition is as elusive to me as these benign beings are in their natural environment. As a boy I was for ever bringing home spawn, tadpoles and frogs to try and keep in my menagerie, but they always escaped and Mum would find them in odd places. When I began carving I made her a necklace with lots of tiny frogs to remind her that I was still a boy at heart. I still love carving frogs as it makes me feel like a boy on a frog expedition again, so I know that they are a personal kaitiaki. Sometimes they become stylised, but more often they appear naturalistic, though I don’t depict them as any specific species, but rather as remembered frog impressions. They are usually small because my favourites were tiny ones we found in a swamp near the beach at Colac Bay.

Frog impressions

Other reptiles I am fascinated by are lizards, which I associate with summer because we hunted for them during holidays in Central Otago, where they bask on the warmed rocks before scurrying off to safety. Lizards are known by several different Máori names, most commonly as mokomoko, but also as ngarara or garara in the south. I later learned that they have traditionally been feared by Máori, because they are linked with Whiro, the god of darkness, evil and death. I was informed that if a lizard is seen, either in the wild or as a carving, it is regarded as a dire warning to leave an area or to leave something alone. However it was reassuring to be told to look for another one, for when a pair of them appear together balance is restored and they become an equally powerful symbol of benevolence. The pair of mokomoko carved into the piece of tooth below have been represented both as we see them, and as they are perceived. By merging the feet into the surface of this carving I was expressing the remarkable ability they have of blending into their background.

The lizard-shaped carving below represents a taniwha, set into a nest of pounamu created by Clem Mellish. Taniwha are fabulous gigantic monsters which appear in Máori lore, often, but not always, in reptilian form. This carving takes the form of a Japanese manju netsuke to acknowledge the similarity of dragon-like monsters in both cultures.

The taniwha below are modelled on the most commonly seen images in ancient Máori rock art, and it is interesting to note that the use of the reverse koru is a prominent feature of their design. The twin-tailed one could be the result of erosion

of the paint, though as several taniwha stories tell how dangerous the swishing tail was, it could depict a warning that the tail seemed to be everywhere when a taniwha was attacked. In 1984 I was invited to stage an exhibition at the Canterbury Museum, and chose to base it on the theme of southern rock art. Because details of pigments and brushes were given to early researchers by descendants of the Waitaha, these paintings have been ascribed to the early Māori colonists who arrived in the Uruao waka under the leadership of Rākaihaitu

The ngarara or lizard forms depicted on the pendant are derived from rock art, but the row of modern-style manaia between them represents the Waitaha descendants who kept their stories alive by passing them orally through the generations. Carving them in this form is my way of saying that descendants are still living with us today. Using a pair of ngarara acknowledges the importance and value of keeping these traditions alive and vital. That message is repeated in the carving below, which uses a notched disc similar to old artefacts, but cuts the painted shapes into the disc. The manaia genealogy notches on the side pieces are carved in the ancient way to give credit to those who brought us the traditions.

Another of the ancient carvings in the Canterbury Museum in Christchurch is one with a stylised bird, thought to be a kākā (below). It was formerly part of the important private collection of the Thacker family at Okains Bay near Akaroa, and its kaitiaki or guardians are now Te Rūnaka o Koukourarata. It has been an inspiration to me ever since I saw a drawing of it and I always revisit it when I have an opportunity. It was carved from a whale tooth, and the artistry of its creator is evident in the way its tail is shaped to maximise the curve of the tooth, as well as the overall form. The detail it still shows indicates the supreme craftsmanship of the carver, and I feel very humble when I consider the skill and creativity that were achieved with stone and bone tools

Eventually I was given a whale tooth similar to that used for the Canterbury Museum kākā carving, and I put it aside with the thought that I could create a similar carving to show the possible form of the original. It languished for a few years as I contemplated what the ancient carver may have been portraying about the kākā. Then while reading the recently published book Kākāpō by Alison Ballance, I thought that the old carving could also have represented another of the native parrots, and if I represented my modern carving as a Kākāpō ‘booming’, then the upsweeping segments could represent the loud bass booms, with serrations along the top of each representing the high-pitched directional sounds. I have no idea what the original carving’s story was of course, but this concept gave me the impetus to carve the one (opposite, top) inspired by that ancient treasure. The stylised face forms that I added along the bottom represent his ancestors, while those along each side represent the descendants and their mates who we hope will continue his line well into the future.

From observers’ accounts of the booming and mating success of Felix, one of the original Kākāpō from Rakiura, I decided to name the Kākāpō after him. I was then fortunate to be loaned some boom sac feathers to accompany his ‘portrait’. In the carving below I have adapted that ancient káká form to depict a giant eagle, and combined it with my stylisation of the indomitable spirit of that bird. The different manaia forms that adorn the sides, both the ancient profile faces on the right and the more modern ones on the left, are used to represent special people known only to the owner. Manaia faces also become devices to hold this taonga on its cord.

The kōkako below acts as both the stopper on the end of a rehu flute and a device to close one nostril when playing the rehu with the breath of the nose. Its origins in the ancient kākā carving are still noticeable, even though it has been adapted to fit its uses, the shape of the whale tooth it was carved from and the whims of the carver

The fragment of an ancient whale tooth carving shown below was possibly created in the same era as southern rock art, and was recently acquired with the Ryman Collection by the Canterbury Museum. As with many of those early carvings we can only speculate on what story it told, but in discussing it with the museum’s senior curator Dr Roger Fyfe, the possibilities raised by our different viewpoints added more intrigue. He pointed out that this section had obviously been cut from a larger rei puta pendant and it appears to have been burnt. The cut would not have been easily made with the tools available then, which raises the question of why it was done. One plausible answer that he put forward was that its mana or power was so great that this was the only way to disempower it.

Early European settlers observed that the rei puta, a pendant made from a single whale tooth, was the most common style of pendant, and they certainly do have a strong presence. I was surprised when carving one in the simplest style (following page) to find that slight differences in the placement of the eyes greatly affected the look of the pendant The fact that rei puta were once so common, and yet few have survived, adds credence to Dr Fyfe’s speculation. As further confirmation, I recall the late Ivan Ehau, who organised the first workshop for the revival of taonga pūoro, explaining that many of the old flutes were destroyed because they were so precious. This was seen as infinitely preferable to them becoming profaned. A few remnants of rei puta from the south are more detailed, like the Canterbury Museum fragment, and people are again asking for these special rei puta pendants to be created. Most of my versions are linked to whales and I have the feeling that traditional rei puta may be derived from the ancient stylised whale pendants described in the next chapter.